Still No Need to Prove an Infringement Case at the Pleading Stage

Intellectual Property News

As the Federal Circuit made clear a few years ago in Nalco Co. v. Chem-Mod, LLC, a plaintiff “need not ‘prove its case at the pleading stage.’” The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure do not require a plaintiff to plead facts establishing that each element of an asserted claim is met. Indeed, the Federal Circuit previously explained in Disc Disease Sols. Inc. v. VGH Sols., Inc. that a plaintiff must only give the alleged infringer fair notice of infringement. Nothing much has changed with the Federal Circuit’s approach to pleading infringement since these two 2018 decisions, so it is puzzling why the appellate court was forced to chastise and reverse the lower court earlier this week for “simply requir[ing] too much” of Bot M8 with respect to its infringement allegations against Sony. In fact, even though the technology in the Bot M8 patents was more complex than the non-invasive medical device at issue in Disc Disease, the hoops that the Northern District of California expected Bot M8 to jump through just to survive a motion to dismiss were certainly remarkable considering precedent on what is not required at the pleading stage. However, this latest decision on pleading requirements does not expound on the previous guidance from the Federal Circuit as to what is required in cases that involve infringement allegations based on more complex technology.

This case initially involved a number of asserted patents, and the infringement claims of all but one were dismissed by the lower court for failure to state a claim. By way of background, the Northern District of California sua sponte required Bot M8 to “explain in [the] complaint every element of every claim that you say is infringed and/or explain why it can’t be done.” Bot M8 complied and submitted a 200+ page complaint. Likely picking up on the overly demanding pleading requirements of the lower court, Sony filed a motion to dismiss the amended complaint. During the oral hearing on the motion to dismiss, the lower court questioned why Bot M8 did not analyze Sony’s source code and later said that Bot M8 should have reverse-engineered Sony’s PS4 software (otherwise known as “jailbreaking” and thought by Bot M8 to be illegal without permission from Sony) and included that evidence in the amended complaint. In other words, the lower court essentially expected Bot M8 to prove its case in its complaint and nothing less would suffice.

The Federal Circuit had no patience for this approach and said that the lower court “demands too much at this stage of the proceedings.” In a more general comment, the panel cautioned that “[t]o the extent this district court and others have adopted a blanket element-by-element pleading standard for patent infringement, that approach is unsupported and goes beyond the standard the Supreme Court articulated in Iqbal and Twombly.” Moreover, it is abundantly clear from this decision that there is no requirement to provide source code at the pleading stage, and lower courts are wrong to demand that a plaintiff do so.

So, we at least can discern from this decision what is not required for this type of technology, i.e., an element-by-element analysis and source code. But, is there any more clarity from this decision as to what is considered a sufficiently pleaded complaint when the technology involved is relatively complex, such as the one in the Bot M8 patents (or, at a minimum, more complex than the non-invasive medical device in Disc Disease)? The short answer is not really. Three years after Disc Disease, the Federal Circuit is still telling us that “the level of detail required in any given case will vary depending upon a number of factors, including the complexity of the technology, the materiality of any given element to practicing the asserted claim(s), and the nature of the allegedly infringing device.” In other words, the allegation can’t be too little (mere recitation of claim elements and corresponding conclusions, without supporting factual allegations) or too much (the kitchen sink approach with inconsistencies) -- it has to be just right for the specific patent claims and accused products at issue. This “Goldilocks Guidance” is simply not the clarity that many had hoped for after Disc Disease.

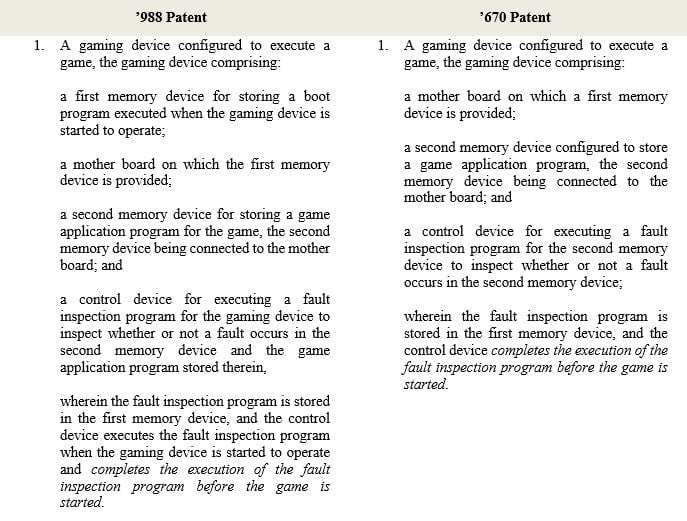

Scrutinizing the claims of the two patents still alive in the Bot M8 lawsuit (U.S. Patent Nos. 7,664,988 (“the ’988 patent”) and 8,112,670 (“the ’670 patent”)) along with the Federal Circuit’s rationale for reversal of the lower court’s dismissal is not particularly enlightening. Indeed, the only element in the claims of the ʼ988 and ʼ670 patents that was focused on by the Federal Circuit relates to the timing of the execution of the fault inspection program (italicized below).

Why is it this particular aspect of the claim and the plaintiff’s identification of numerous error codes displayed before the game starts that saved the day for these two patents? What if the plaintiff only identified one error code instead of 12? Or, what if the plaintiff merely provided “The PlayStation CPU will execute the fault inspection program when the device is booted up and before the game is started” without any mention of any specific error codes? Why wasn’t “the inspection for both the memory device and the game stored therein” sufficient if an element-by-element analysis is not required?

Indeed, even with this newest precedential opinion available, we are left wanting more in terms of unambiguous guidance on pleading requirements from the Federal Circuit. And, similar to our conclusion drawn after Disc Disease, until more specific guidance is available, it is probably still wise to include factual allegations for each asserted claim and every accused product able to be identified (based upon publicly available information known at the time of filing the complaint), regardless of the complexity of the technology involved.