The India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor: Prospects and Challenges for U.S. Businesses

Bradley Intelligence Report

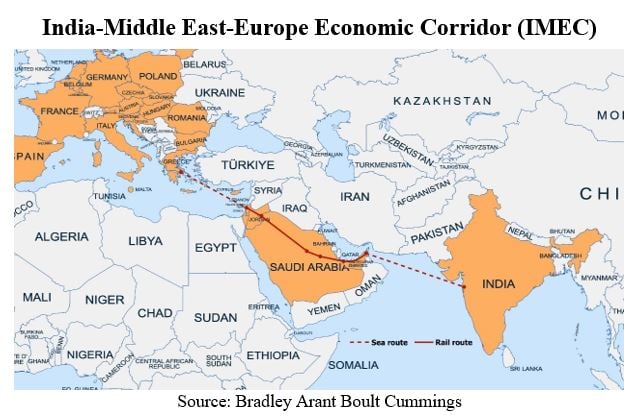

Perhaps the most salient development to come from the G-20 Summit in New Delhi last month was the announcement of the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), an ambitious multibillion-dollar connectivity project linking India to Europe. The agreement, co-signed by India, the United States, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, France, Germany, Italy, and the European Union, sets out a plan to connect a series of railway and shipping lines spanning from India’s western coast through the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Israel to Europe. The project has been positioned as an alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), in which the U.S., India, and some EU member states are notably non-participants, and which China has used to build deep global relationships. Despite recent uncertainties stemming from the ongoing Israel-Hamas war, the IMEC holds significant potential in its ability to provide an alternative to Chinese infrastructure investment, reducing business costs, improving logistical efficiency, and creating jobs for the benefit of businesses and individuals alike.

Reassessing Traditional Trade Venues

According to the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) released by the White House, the IMEC will be composed of two separate corridors, with the eastern flank connecting India to the Arabian Peninsula and the northern flank connecting the Arabian Peninsula to Europe. Including a railway that will provide a reliable and cost-efficient, cross-border, ship-to-rail transit network delivering goods and services to, from, and between India, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Israel, and Europe, the route notably avoids the congested Suez Canal that has served as a traditional point for trade in and around the Middle East. As a result, it is estimated that goods could reach Europe from Mumbai 40% faster compared to the Suez Canal path, cutting shipping costs, time, fuel usage, and trade facilitation, while enhancing efficiency and securing regional supply chains. The corridor will also make use of digital and financial networks and incorporate clean energy transport and innovation for developing advanced clean energy technologies.

Despite these aims, the project faces skepticism over its feasibility, with critics claiming that the results of its implementation may not live up to the political hype. Firstly, the loading and unloading costs involved and time required to stop at each port along the route could end up undermining the estimated costs and time saved. Secondly, the unstable security environment in Jordan due to persistent economic challenges and a high proportion of refugee populations, as well as the corridor’s proximity in Israel to the West Bank that makes it vulnerable to terrorist attacks, also present hurdles to its efficacy. Moreover, though member countries have announced $20 billion for the project, the IMEC (unlike the BRI) will rely primarily on funding from private investors, who may find the cost and lengthy duration of the project prohibitive. Regulations, taxation, and customs procedures will need to be aligned as well, and above everything, the success of the project will be determined by economic growth and demand in India, the Middle East, and Europe, which are contingent in turn on global economic recovery. Given the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and flareups in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict that have all occurred in the early years of this decade, it will likely take time for the corridor’s aims to be fully realized and for investors to see a substantial return on their financial contributions.

Geopolitical Implications

Much like the BRI, the IMEC serves as much of a political purpose as it does economic. Beijing’s growing influence in the Middle East, as evidenced by its recent moves, including its role in brokering an agreement to restore diplomatic ties between Iran and Saudi Arabia, has unnerved Washington. Owing to growing geopolitical tensions between the two superpowers over the past decade and an American motivation to limit economic reliance on Beijing, the initiative demonstrates the Biden administration’s resolve to reassure U.S. allies and partners in the Middle East of Washington’s commitment to the region. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and European countries such as Italy and Greece have participated in the BRI, though its image has been tainted by debt trap tactics in countries like Sri Lanka, making the time ripe for a viable U.S.-led alternative. Similarly, India refused to join the BRI from its onset due to objections over the project running through territory in Kashmir disputed by New Delhi. Violent border clashes between India and China in recent years, as well as anxieties over China’s growing economic influence and strategic footprint in South Asia, have prompted Indian leaders to improve ties with the West, especially the United States. In 2021, the I2U2 Group was formed as a multilateral initiative between the U.S., India, the UAE, and Israel to enhance cooperation across multiple domains with private sector capital, while India has actively participated in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (or the Quad) alongside the U.S., Japan, and Australia since the grouping’s re-establishment in 2017. New Delhi shares Washington’s perception of Beijing as a growing strategic threat and may seek to utilize the IMEC as an opportunity to rival the influence of China in the Middle East, which has traditionally been an important energy source for the South Asian nation.

On the other hand, Saudi Arabia and the UAE take a different view on the IMEC. Rather than seeking confrontation or competition with China, Gulf states look to the project as an opportunity to aid ongoing efforts to diversify their economies away from fossil fuels. The potential to boost tourism, investment, and logistics, while enabling a domestic energy transition toward renewable sources aligns neatly with the Saudi Vision 2030 set forth by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. In addition, the IMEC would grant these countries greater access to an emerging Indian market that has been growing more lucrative by the year. Essentially, the project represents an invaluable opportunity for the Gulf states to maximize their geopolitical pull across multiple regions, by further establishing themselves as bridges between Asia and Europe. While officials in Washington and European capitals may hope for the IMEC to dent China’s geoeconomic rise in the Middle East, they will quickly come to the realization that their Gulf partners in the project sought to join with substantially different intentions.

Opportunities for U.S. Businesses

While the politics are complicated and an important driver of the IMEC, the economic opportunities are evident. The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is one of the least economically integrated regions in the world, with intra-regional trade only accounting for about 8% of both exports and imports, while substantial non-tariff trade barriers negatively impact economic development. In turn, the IMEC envisions unlocking trade by easing the movement of goods at the border and focusing on reducing overall trade costs. Oil-producing states, as they attempt to diversify their economies, have strong incentives to invest in projects that will expand their access to new markets for new products. Likewise, India, which historically leaned towards economic protectionism, will benefit from increased connectivity as it liberalizes its economy. The spillover effect for countries along the corridor will be positive, going beyond developing infrastructure to support the trade corridor (e.g., linked transportation networks, energy grids, and telecommunication lines) to include incentives for new free trade zones and manufacturing hubs.

The opportunities for U.S. businesses come from both the supply and demand sides. The Ukraine war and the deterioration of bilateral relationships with Russia and China, on the heels of a global pandemic, have reinforced the imperative for diversified and secure supply lines. India is currently among the world’s fastest growing economies, with prospects emerging from the immense growth occurring in the country’s manufacturing sector and consumer demand. As India continues to reorient towards the West, partnership opportunities in technology, food security, clean energy, and manufacturing thrive. Though U.S.-India trade was a relatively modest $191 billion in 2022, experts see the possibility of it doubling with the reduction of trade barriers and closer cooperation in defense, the digital economy, energy transition, and advanced technology. The Gulf states are experiencing dynamic growth, unleashed through new national economic development policies to boost domestic innovation, develop manufacturing and technology hubs, and educate and train a modern workforce, and the prospects for U.S.-based firms to attain synergies through economic engagement with the region are ripe.

With the opportunities outlined, the IMEC will more likely than not take years to develop, while the end state may be quite different from the current vision, as regional initiatives such as the Abraham Accords (normalization between Israel and its neighbors) and the I2U2 Group reshape trade relations. Iran presents a substantial variable as a disruptive player or potential new regional market should Tehran shed its Islamic revolutionary goals. The most important takeaway for U.S. businesses is that India and MENA countries are rapidly opening their economies, creating a plethora of new trade opportunities; 10 years ago, an India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor was not even a pipe dream.